GOOD MORNING SNAP SHOT STARS!

Instead of a Snapshot, I am sharing a few pieces I’ve researched regarding reparations and how land should be included in the conversation. This will be apart of an ongoing series Exposing the Insidious History of Racism: False Crimes and The Black Code

ARE REPARATIONS AND LAND RESTORATION POSSIBLE IN THE UNITED STATES?

The issue of reparations for Black people has been a hotly debated topic for many years. Some people believe that the United States government owes a debt to Black Americans for the centuries of slavery, discrimination and destruction of established Black towns [before] and after the reconstruction era they have faced, while others believe that reparations would be unfair to white people or would not be effective in addressing racial inequality.

In recent years, the conversation about reparations has gained new momentum. In 2023, California's reparations task force recommended that the state provide billions of dollars in reparations to Black residents. And in Congress, Rep. Cori Bush (D-MO) has introduced legislation that would provide $14 trillion in reparations to Black Americans.

There are many different proposals for how reparations could be implemented. Some people have suggested that reparations should be paid in the form of cash payments, while others have suggested that they could be used to fund programs and initiatives that benefit Black communities. There is no one-size-fits-all solution, and the best approach to reparations would likely involve a combination of different methods.

AFTER SLAVERY & WHITE ATTEMPTS TO UNDO THE RECONSTRUCTION ERA

The destruction of Black towns was a tragedy, but it is important to remember the resilience of Black Americans. Despite the hardships they have faced, Black Americans have continued to build thriving communities.

After the Civil War, many Black Americans left the plantations where they had been enslaved and formed their own towns. These towns were often located in the South, and they became thriving communities. However, in the late 19th century, many of these towns were destroyed by white mobs.

There are many reasons why white mobs destroyed Black towns. Some white people were angry that Black Americans were no longer enslaved, and they wanted to punish them. Others were afraid of Black economic and political power. And still others simply wanted to maintain white supremacy.

The destruction of Black towns was a devastating blow to Black communities. It destroyed homes, businesses, and schools. It also displaced thousands of people. And it sent a message that Black Americans were not welcome in the United States.

The destruction of Black towns is a reminder of the long history of racism in the United States. It is also a reminder of the resilience of Black Americans. Despite the hardships they have faced, Black Americans have continued to build thriving communities.

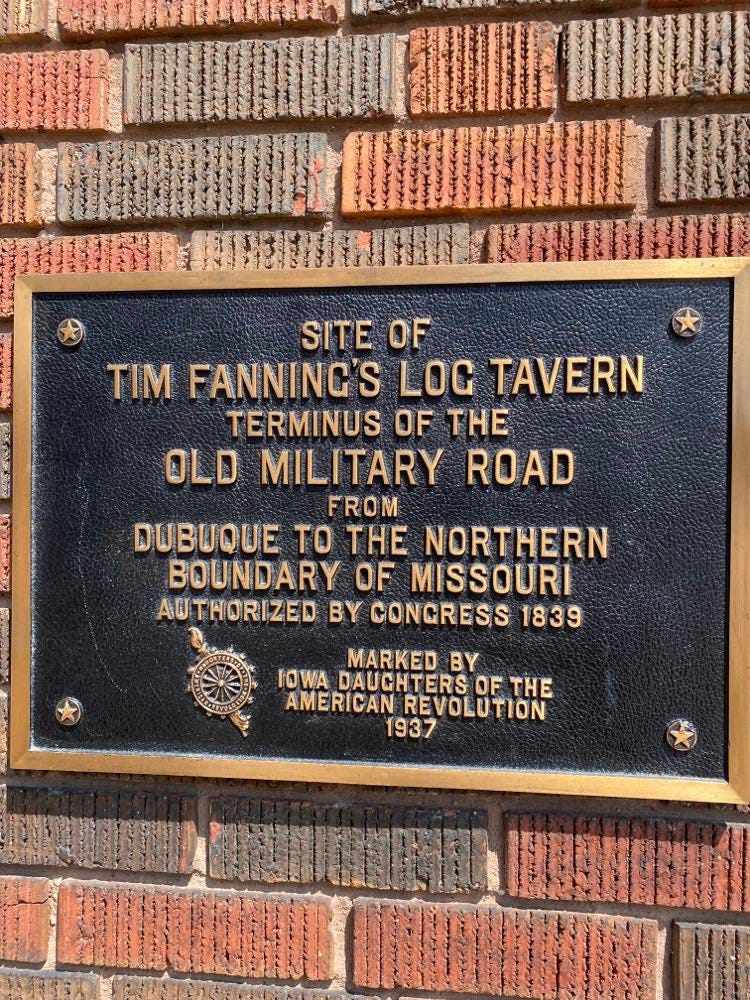

I live in a town with a dark history and a well hidden one. Recently there was a Black Heritage Survey which uncovered stories of the first Black settlers in the Michigan Territory in the early 1800’s. The story which fascinates me the most is the story of Nathaniel ‘Nat’ Morgan and his lynching (pre-Civil War), that set a precedent of how well received free Black people were in the town of Dubuque. Nathaniel Morgan owned property and today there is a plaque on that very building with a year before the murder and according to the history of Lot one researched by genealogist Riki King, Roots to Branches Genealogy, and the Nathaniel Morgan Memorial Committee (Ernestine Moss) they’ve discovered Nathaniel & Charlotte Morgan owned Lot One until 1840.

COULD NATHANIEL MORGAN BE A VICTIM OF LAND THEFT?

In my opinion and research, the Lynching of Nathaniel Morgan is eerily similar to other ‘stories’ across the country when a Black person is a victim of a White citizen falsely accusing them of a crime or a White Woman reports a false accusation of being violated by a Black man. When the stories are over and lives are lost, Black people flee and White citizens pillage, pilfer and build on land that was left behind.

Story of Black Settlers & Nathaniel Morgan

Black Dubuquers were among the City's first non-native settlers in the 1830s. Dubuque's Black population was the highest in the region that would become Iowa. Our Black population levels rose and fell over the next 150 years. This page explores Dubuque's Black heritage from 1830-1980, focusing closely on the West 8th Street Neighborhood, historically settled by our Black residents.1

Among the 1830s non-native settlers of Dubuque were Charlotte and Nathaniel Morgan. Charlotte was listed as a financial contributor to the first church in Iowa, erected at the northwest corner of 6th and Locust, which opened in 1833. (By 1835, the Morgans were landowners of Lot One in the Village of Dubuque.)

Was it all a lie that lead to Nathaniel’s death?

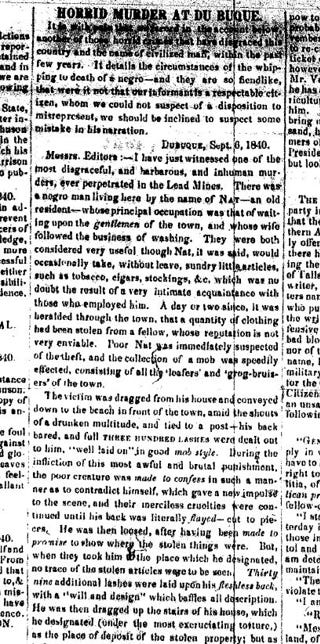

Despite being a founder of Dubuque, early landowner and contributor to the community, in 1840, Nathaniel Morgan, husband to Charlotte, was brutally lynched by a group of men accusing him of stealing clothes from the hotel where he worked. The men were acquitted, despite their crime of a violent, public murder.

Story of Lot One and Possible Connection to Nathaniel’s Lynching

CHARLOTTE & NATHANIEL MORGAN

The Morgans were founders of Dubuque. Charlotte is listed as a financial contributor to the first church in what would become the state of Iowa, at 6th and Locust Streets, which opened for services in 1833. By 1835, she and her husband Nathaniel purchased "Lot One in the Village of Dubuque", a prominent property near the river at the corner of 1st and Main Streets, the quintessential center of any community, and certainly Dubuque. They were not alone as Black landowners at the center of Dubuque, joined by the Aaron family and others nearby in Dubuque's early days.

Resentment took hold of members of the White community. In 1840, newspaper accounts in Dubuque and Galena describe the lynching of Nathaniel, brutally beaten and dragged around the community until his death, and then being reposited by the murderers to Charlotte at their home. Colonel Paul Cain, a thirty-five-year-old miner from New York, the commander of the local militia unit and a failed candidate lead the charge

Colonel Cain and several other men of the mob were tried for murder but eventually were acquitted, on account that the intention to commit murder was not proven.

Charlotte continued to live in Dubuque, listed in the 1850 census living with two miners, and in the 1863 directories with another man named Coren Morgan, who may have been brother to Nathaniel. She was no longer a land owner.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Creative Shift to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.